Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists at the Whitney

March 13, 2020 § Leave a comment

“With more than 200 works by sixty Mexican and American artists, Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945 reorients art history, revealing the profound impact that the leading Mexican muralists—José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, known as “los tres grandes”—had on the course of American art. From Jackson Pollock to Jacob Lawrence to Marion Greenwood, artists in the United States were inspired by their Mexican counterparts to transform elements of national history and everyday life into epic narratives of strength and endurance. Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945, on view February 17–May 17, 2020.” -Whitney Museum of American Art

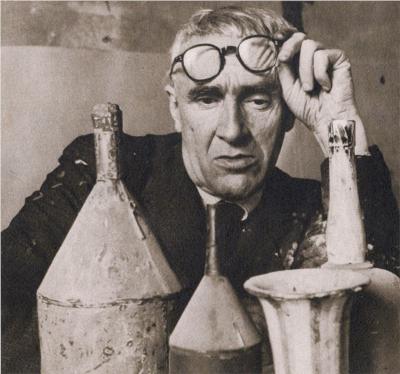

The Gnosticism of Giorgio Morandi

May 29, 2019 § Leave a comment

“For students of painting (Morandi) continues to question, allowing us through painted palimpsests to see him in the act of deciding. In spite of a natural reclusive inclination, he showed us what it is to believe in painting as a way of life, to love its tattletale evidence of our humanness….In one completed painting exists a layering of faltering probes: passage over passage of stutterings, mutings, bumblings, corrections, slaps and sludges which finally slouch towards a homemade hand-hewn idealization. This is a stirring and captivating demonstration of how to labor a painting through to a life of its own. It is as if the actual birth process of a painting has been anthologized.” –Wayne Thiebaud, on Morandi

Read Wayne Thiebaud’s entire article on Giorgio Morandi, published in the New York Times, November 15, 1981, on occasion of the retrospective of Morandi’s work at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

Richard Cook’s Dreams and Reflections

May 25, 2019 § 2 Comments

“In one sense (paintings) are dreams and they’re reflections and they’re memories, and they become more so; but they are crucially tethered to a particular place, all of them, to the point I could give grid references for all of these paintings.

I think the thing about painting is that it’s always out of reach slightly… one reaches for something… like the horizon, and yet one can never have it, one can never even touch it; one sort of yearns towards it and that’s all one can ever do.”

Fascinating Rythms

April 29, 2019 § Leave a comment

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

“… All you need now is to stand at the window and let your rhythmical sense open and shut, open and shut, boldly and freely, until one thing melts in another, until the taxis are dancing with the daffodils, until a whole has been made from all these separate fragments.” -Virginia Woolf, A Letter to a Young Poet

Children of a certain age are strangely masterful in wielding a brush. They don’t have to be told what to do, or how to do it. Mark-making is a deep, instinctual, and self-sufficient pleasure as old as the human race. Some manage to hold on to the natural feeling for rhythm, movement and relationship in art making as they leave childhood, but too often it becomes buried in the adult whose only model for form-making is the smooth, indiscriminately detailed facture of photography. Re-awakening these dynamic instincts should be as important a goal to the student of painting as learning to see and mix color.

The experiments of artists in the early 20th century are instructive for unpacking this business of rhythm and movement in painting. Abstract forces exist in all painting, and in any view of nature, but they often are disguised, especially to the novice, by the dominance of illusionistic concerns. In the early decades of the 20th century, just as the theories of Einstein began to undo and reshape traditional notions of time and space, Modern art movements such as Cubism, Futurism, De Stjil, and Constructivism began to reorient the focus of painting away from the outward appearance of solid matter to the internal dynamics of pictorial structure. The fractured spaces of George Braque and Picasso, and the reductive verticals, horizontals and diagonals of Theo Van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian began to speak of an energetic reality behind appearances.

Jack Boul, one of my teachers in grad school, made a comment that I think brilliantly frames a fundamental problem of painting. He said, “We sense the structure in early Mondrian. His line first represents a vertical, then a division of the picture space, then a tree. Most people just paint the tree.”

If the Renaissance, and the centuries of pictorial traditions it fostered, were based on the assumption of a solid world composed of discreet entities in a measurable space, the new spirit in painting was informed by the scientific revelation that matter is not solid at all – it’s energy. E=mc2. Painting’s formal language becomes a corollary to this new vision – the structured, dynamic rhythms of the physical universe played out on the artist’s canvas.

Landing a Plane in High Winds: Painting and Photography

March 6, 2019 § Leave a comment

Eugene Delacroix

Eugene Delacroix

“From today, painting is dead.” (Paul Delaroche after the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839.)

“How difficult it is to learn not to see like cameras…the camera sees everything at once. We don’t.” -David Hockney

Photography and painting have long contended over a common territory, the faithful representation of reality. Ever since Leonardo da Vinci declared that the highest objective of painting was to create convincing illusions of volume, light and depth on the flat picture surface artists have sought that ideal through assiduous study, visual acuity and manual skill. This centuries old assumption regarding the goal of painting led people to declare the death of painting when the first photographic process emerged in the early 1800s.The camera, with the press of a button, achieved effortlessly what once took an artist years to perfect.

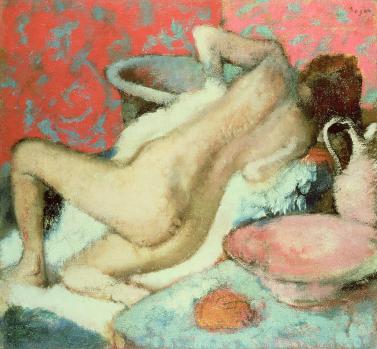

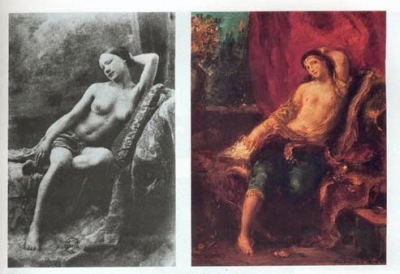

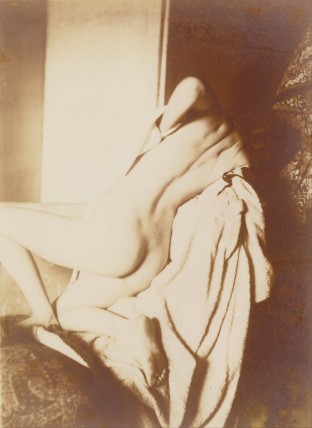

Early 19th century photographers struggled to distinguish themselves from the mere button-pushers by finding the Art in these new processes. They did this largely by imitating painting, in a sense appropriating the language of image making that centuries of painters in the west had established. Painters, on the other hand, were quick to use the new medium as an assist in painting. Delacroix is an early example, as is Degas, who left thousands of photographs in his studio at his death in 1927. In these documents we recognize the models for some of his best known paintings. Bonnard and Vuillard also left photographs of their models. And well before the advent of photography the camera obscura and camera lucida shaped the painterly visions of Vermeer and many of his contemporaries.

At the bottom of both of these arts, painting and photography, is a basic human fascination and delight in the visual feast that our eyes lay before us from the moment we wake up in the morning. But the similarity between the photographer’s art and the painter’s ends as soon as they take up their respective tools. Students of painting, struggling to appropriate the skills and instincts for making their art, especially need to understand this disparity, and why working from direct observation is still crucial.

A camera, as Hockney suggests, produces an instantaneous image, formed in a fraction of a second by a mechanical, or these days, an electronic mechanism. A painting, by contrast, unfolds over a long period of time by slow, manual manipulations of paint. Taking a photograph can often be like casting a fisherman’s net. A lot of stray fish end up in the catch. The casual photographer, unlike the painter, may not have been cognizant of everything that the net of his camera has recorded. A painter, on the other hand, must visit every part of her subject and her canvas, making decisions inch by inch: what color, how dark, how warm or cool, how intense, what texture, what shape and quality of edge. The painter attends to the subject’s totality; not just to isolated objects but to the whole spatial ensemble. The quality of that attention is laid into the paint itself at the moment of making, like jazz improvisation. A stroke of paint is a deposit of the painter’s consciousness on the physical matter of the canvas. By nature the process is accumulative; it builds slowly and circuitously to its climax. Even more importantly, the painter may destroy the image repeatedly on her way to some final resolution. Manipulating photographic imagery in the darkroom or on a computer can approximate this sort of open-ended search but there are important distinctions. With a painting, there’s no original negative, print, or saved state to return to when the piece goes off the rails.

In photography the natural hierarchies of light impersonally press their familiar structure onto the image. The photographer guides the camera but the instrument does the rest. The painter by contrast must shape the image by hand; must find the structure all while being buffeted by the anarchy of subjective experience. Painting is like trying to land a plane in high winds. You move the thing forward but it shifts constantly off the path. The momentary encounter with a certain part of the subject, a chair, say, may suddenly open a trap door to childhood memories – the painter can lose the vision of the whole and begin to dote on the individual object. The necessary distancing that allows her to see the relationship of the chair to the rest of the painting is, for that moment, lost. She must then find her way back, repeatedly, to some sense of a hierarchy knitting together the parts of her painting. This is the great advantage of painting, but it is also why paintings can go so wrong. There are so many more opportunities to make individual decisions that don’t relate well to other decisions. The camera, on the other hand, captures a seamless, familiar reality, leaving it to the photographer to concentrate on selection of the motif.

The objectifying, organizing power of the photograph can be very seductive for painters, especially students, whose image making culture is dominated by the pervasiveness of internet imagery. Photoshop and its imitators, and platforms like Instagram put tools for making images into everyone’s hands. How different and difficult is the painter’s long study, training and practice with manipulating color in order to realize a particular and individual vision. Who today has the patience to apply himself to this archaic practice, and to suffer through the humbling mediocrity of much of his efforts until some success is achieved? When we work from photographs the hard part of translating the multiple perspectives and shifting aspects of the three-dimensional world into the flat image has already been done for us. In the absence of any formative contact with the long traditions of art, or lacking familiarity with painting’s idioms of form-making, students can fall into the trap of simply appropriating the language of photography with its seductive similitude, intense detail and texture.

That’s the essential difference between how the student tends to use photographs in painting and how the masters did it. The vision of artists like Degas and Vuillard was shaped by the study and practice of painting, and by deep contact with the art-making traditions that preceded them before they discovered photography. They knew, or felt how they wanted their paintings to look, and what their paintings had to do in terms of its unique formal language. In the hands of a master, the photographic information is conformed to the painterly vision. For the student, all too often, the instantaneity of the photograph substitutes for the deeper vision that can only be developed through a cultivated love for the medium of painting.

Edgar Degas

“The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work…”

September 8, 2018 § 1 Comment

…is the title of a book by Alain de Botton. Botton describes the conflicted relationship to work that many people experience in their lives, and he draws a poignant comparison with the experience of the craftsman’s work.

In a job, he says, “…Our exertions generally find no enduring physical correlatives. We are diluted in gigantic intangible collective projects, which leave us wondering what we did last year and, more profoundly, where we have gone and quite what we have amounted to. We confront our lost energies in the pathos of the retirement party.

How different everything is for the craftsman who transforms a part of the world with his own hands, who can see his work as emanating from his being and can step back at the end of a day or lifetime and point to an object – whether a square of canvas, a chair or a clay jug – and see it as a stable repository of his skills and an accurate record of his years, and hence feel collected together in one place, rather than strung out across projects which long ago evaporated into nothing one could hold or see.”

Mistakes

November 5, 2016 § 2 Comments

“When you hit a wrong note, it’s the next note that you play that determines if it’s good or bad.” -Miles Davis

How often when painting do we put down a color patch, a mark, or a brushstroke that just doesn’t hit the note we’re after? Too often. The many ways that our moves on the canvas can be off are dauntingly large. The value can be too dark or too light. The hue and temperature can fail to mesh with the existing colors. They might pop out or sink in, or create a jarring discord. The drawing – things that affect the rightness of proportion, or the readability of the space – can go off track, creating strange distortions.

Our first reaction is to think we’ve made a mistake! A mistake is something that is not correct, an inaccuracy. But what if we change the way we look at, and think about, this apparent disaster? Learning to paint is not just about learning techniques, it’s about appropriating new eyes and a new mind for considering this fraught enterprise in which we’re engaged. What if we stop thinking about that bad color note as an isolated “incorrectness” and instead consider the whole context in which this misstep appears defective? Sometimes a mistake is a gift in disguise.

In the end, every color we put on the canvas is simply a fact. Every color is a verb that acts. That patch of paint we’ve just applied to the canvas has a color hue and temperature, a value and an a level of saturation or intensity. Further, and more importantly, it’s appearance in our painting is a function not just of pigment but of relationship. Leonardo was perhaps the first artist to note the phenomenon of relativity in color and value. A color, he says, appears as it does according to the context in which it is placed, and that same color can look very different depending on the other colors it is seen against. Delacroix, embracing this phenomenon of painting said, famously, “Give me mud, and with it I will paint the flesh of Venus, if you allow me to surround it as I please.”

Miles Davis, the great jazz trumpeter, gives us a new way to think about these so-called mistakes. Everything depends, he says, on what comes next. The next notes you play can either confirm and compound the sense of wrongness, or they can begin to welcome that mistake into the ensemble and make it meaningful, even revelatory. A mistake is what we make when we’re following a preconceived aim and a piece of the puzzle doesn’t fit. If we stay open to what happens we have the potential of following the work into some very interesting territory. The many gaps between what we think we’re doing and what actually happens is where a lot of the excitement of painting happens. Thinking of painting as a kind of visual improvisation, rather than a step by step process, opens new doors. It gives us a whole different set of sensitivities with which to solve the problems of a particular painting.

Wayne Thiebaud’s Painted World

September 8, 2016 § Leave a comment

I was privileged as a young student to participate in a workshop at Mountain Lake in Virginia in the early 1980s, organized by my teacher, Ray Kass, from Virginia Tech. I imagined that Thiebaud would be a kind of Oscar Wilde-like character, as colorful and flamboyant as his delicious paintings of pies and cakes that were very much defining the contemporary art world at that time, the world that I, as a young painter, was preparing to enter. What I found instead was a deeply humble man who wasn’t much interested in talking about himself, his work, or his reputation. We spent an evening looking at old, brown masters of the past – Chardin, Rembrandt, Tintoretto and others – while Thiebaud held forth on his deeply held belief in the need for painters to work at acquiring the disciplines of looking and seeing the world around them. Here’s an instructive excerpt of a talk by Wayne Thiebaud given at the New York Studio School in 1999. In it he articulates in his wonderfully clear, no-nonsense way, some of the same values that he shared with us those many years ago.