Landing a Plane in High Winds: Painting and Photography

March 6, 2019 § Leave a comment

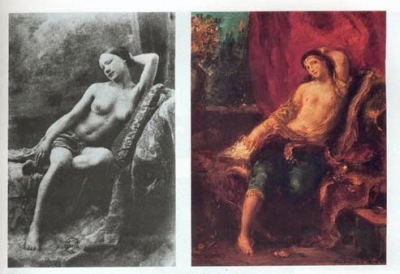

Eugene Delacroix

Eugene Delacroix

“From today, painting is dead.” (Paul Delaroche after the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839.)

“How difficult it is to learn not to see like cameras…the camera sees everything at once. We don’t.” -David Hockney

Photography and painting have long contended over a common territory, the faithful representation of reality. Ever since Leonardo da Vinci declared that the highest objective of painting was to create convincing illusions of volume, light and depth on the flat picture surface artists have sought that ideal through assiduous study, visual acuity and manual skill. This centuries old assumption regarding the goal of painting led people to declare the death of painting when the first photographic process emerged in the early 1800s.The camera, with the press of a button, achieved effortlessly what once took an artist years to perfect.

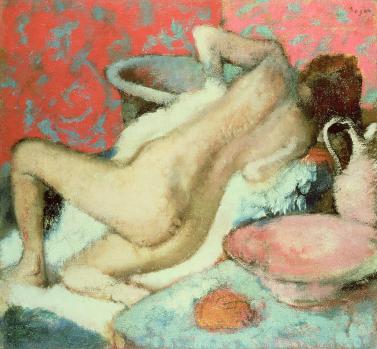

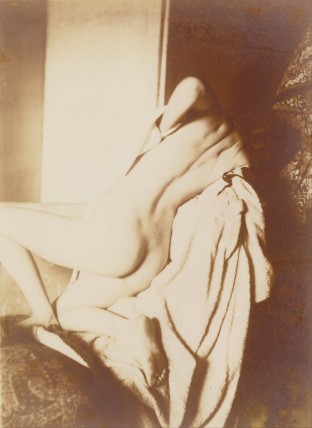

Early 19th century photographers struggled to distinguish themselves from the mere button-pushers by finding the Art in these new processes. They did this largely by imitating painting, in a sense appropriating the language of image making that centuries of painters in the west had established. Painters, on the other hand, were quick to use the new medium as an assist in painting. Delacroix is an early example, as is Degas, who left thousands of photographs in his studio at his death in 1927. In these documents we recognize the models for some of his best known paintings. Bonnard and Vuillard also left photographs of their models. And well before the advent of photography the camera obscura and camera lucida shaped the painterly visions of Vermeer and many of his contemporaries.

At the bottom of both of these arts, painting and photography, is a basic human fascination and delight in the visual feast that our eyes lay before us from the moment we wake up in the morning. But the similarity between the photographer’s art and the painter’s ends as soon as they take up their respective tools. Students of painting, struggling to appropriate the skills and instincts for making their art, especially need to understand this disparity, and why working from direct observation is still crucial.

A camera, as Hockney suggests, produces an instantaneous image, formed in a fraction of a second by a mechanical, or these days, an electronic mechanism. A painting, by contrast, unfolds over a long period of time by slow, manual manipulations of paint. Taking a photograph can often be like casting a fisherman’s net. A lot of stray fish end up in the catch. The casual photographer, unlike the painter, may not have been cognizant of everything that the net of his camera has recorded. A painter, on the other hand, must visit every part of her subject and her canvas, making decisions inch by inch: what color, how dark, how warm or cool, how intense, what texture, what shape and quality of edge. The painter attends to the subject’s totality; not just to isolated objects but to the whole spatial ensemble. The quality of that attention is laid into the paint itself at the moment of making, like jazz improvisation. A stroke of paint is a deposit of the painter’s consciousness on the physical matter of the canvas. By nature the process is accumulative; it builds slowly and circuitously to its climax. Even more importantly, the painter may destroy the image repeatedly on her way to some final resolution. Manipulating photographic imagery in the darkroom or on a computer can approximate this sort of open-ended search but there are important distinctions. With a painting, there’s no original negative, print, or saved state to return to when the piece goes off the rails.

In photography the natural hierarchies of light impersonally press their familiar structure onto the image. The photographer guides the camera but the instrument does the rest. The painter by contrast must shape the image by hand; must find the structure all while being buffeted by the anarchy of subjective experience. Painting is like trying to land a plane in high winds. You move the thing forward but it shifts constantly off the path. The momentary encounter with a certain part of the subject, a chair, say, may suddenly open a trap door to childhood memories – the painter can lose the vision of the whole and begin to dote on the individual object. The necessary distancing that allows her to see the relationship of the chair to the rest of the painting is, for that moment, lost. She must then find her way back, repeatedly, to some sense of a hierarchy knitting together the parts of her painting. This is the great advantage of painting, but it is also why paintings can go so wrong. There are so many more opportunities to make individual decisions that don’t relate well to other decisions. The camera, on the other hand, captures a seamless, familiar reality, leaving it to the photographer to concentrate on selection of the motif.

The objectifying, organizing power of the photograph can be very seductive for painters, especially students, whose image making culture is dominated by the pervasiveness of internet imagery. Photoshop and its imitators, and platforms like Instagram put tools for making images into everyone’s hands. How different and difficult is the painter’s long study, training and practice with manipulating color in order to realize a particular and individual vision. Who today has the patience to apply himself to this archaic practice, and to suffer through the humbling mediocrity of much of his efforts until some success is achieved? When we work from photographs the hard part of translating the multiple perspectives and shifting aspects of the three-dimensional world into the flat image has already been done for us. In the absence of any formative contact with the long traditions of art, or lacking familiarity with painting’s idioms of form-making, students can fall into the trap of simply appropriating the language of photography with its seductive similitude, intense detail and texture.

That’s the essential difference between how the student tends to use photographs in painting and how the masters did it. The vision of artists like Degas and Vuillard was shaped by the study and practice of painting, and by deep contact with the art-making traditions that preceded them before they discovered photography. They knew, or felt how they wanted their paintings to look, and what their paintings had to do in terms of its unique formal language. In the hands of a master, the photographic information is conformed to the painterly vision. For the student, all too often, the instantaneity of the photograph substitutes for the deeper vision that can only be developed through a cultivated love for the medium of painting.

Edgar Degas

“Le Petit Tache:” Divisionist Technique and Optical Mixing

February 7, 2011 § 5 Comments

Impressionist & Divisionist Technique

Landscape was the genre in which divisionist techniques were born and most developed, beginning with Turner and Delacroix who began to exploit the observations and theories of Chevreul and Goethe on the optical mixing of color by painting with distinct touches of unblended paint, side by side, allowing the color to “mix” in the eye.

The work of Turner and Delacroix, as well as that of Goethe and Chevreul in the early 19th century, had a profound impact on Monet, Pissaro, Sisley, Renoir, and others of the group that later became known as “Impressionists.” As students, their academic training taught them to shade forms off into brown and black in the shadows. These young painters could see that shadows were actually colored, and that, in fact, the whole visual field was shimmering with color sensation. Local color, the notion that things have a distinct, unchanging color, was shattered in the new awareness of how color, light, and context influence the perception of color. Their dissatisfaction with the limitations of academic teaching led them out of the studios into nature to work out a new way of painting based on the broken touch.

The technique itself was not new but its application was. The Impressionists built on an academic method widely taught in the ateliers of Paris known as the “petit-tache,” or little touch, a technique of applying unblended touches of color which later would be blended with a soft, badger-hair brush to disguise the effect and create a smoother, more refined look. The Impressionists were reviled, not only for their subject matter, which confronted every day realities of contemporary life as opposed to the classicizing conceits of academic painting, but also for exhibiting finished works with this broken touch, a direct confrontation to the tastes of the day. Seurat, and Signac developed the divisionist technique into the style known as Pointillism, based on their growing interest in the scientific application of color physics to painting.

Painters like Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Serusier, Bonnard, and many others, were less interested in the science of color than they were in its emotional impact, and pushed color saturation into new subjective realms, developing very personal styles that derived from the use of the “petit-tache.”

- Rembrandt

- Frans Hals

- Frans Hals

- Turner

- Turner

- Turner

- Delacroix

- Boudin

- Boudin

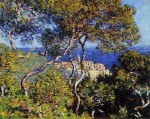

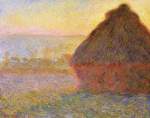

- Monet

- Monet

- Monet

- Monet

- Cassatt

- John Singer Sargent

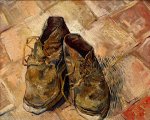

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Seurat

- Seurat (detail)

- Seurat

- Seurat

- Signac

- Signac

- Signac

- Signac

- Gauguin

- Serusier

- Bonnard

- Bonnard

- Bonnard

- Jake Berthot

- Jake Berthot

- Jake Berthot

- Chuck Close

- Ann Gale

- Ann Gale

- Alex Kanevsky

- Alex Kanevsky

- Alex Kanevsky