“Let Us Believe in Art”

March 8, 2014 § 3 Comments

Is being an artist today a selfish pursuit? If a painter does not address the political, environmental, or social ills of the age through painting is he or she just a naive Peter Pan, an escapist, or a wishful thinker painting pretty pictures while the world goes up in flames? What possible value does art have in a world so beset by problems? Every art student asks these questions at some point. Shouldn’t I be doing something to help the world? In the face of the unprecedented human misery of our time shouldn’t we, as artists, forget about our selfish visions and ideals about beauty and serve humanity?

In 1915 World War I was raging across Europe. Claude Monet, then 75 years old, wrote the following in a letter to Raymond Keochlin, an art collector:

“Yesterday I was able to resume work, which is the only way to avoid thinking of these troubled times. All the same I sometimes feel ashamed that I am devoting myself to artistic pursuits while so many of our people are suffering and dying for us. It’s true that fretting never did any good. So I’m pursuing my idea of the Grande Decoration. It’s a very big undertaking, particularly for someone my age, but I have every hope of succeeding if my health doesn’t give out. As you guessed it, it’s the project that I’ve had in mind for some time now: water, water-lillies, plants, spread over a huge surface. Let’s hope that event’s will take a turn for the better. I’d be glad to see you and show you the beginnings of this work. Friendly greetings, Claude Monet”

Monet’s Water Lillies at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC.

Another 19th century artist, the American painter George Inness, had some things to say about the higher functions of art in a society. He said, “Let us believe in Art, not as something to gratify curiosity or suit commercial ends, but something to be loved and cherished because it is the Handmaid of the Spiritual Life of the age… The true use of art is, first, to cultivate the artist’s own spiritual nature, and, second, to enter as a factor in general civilization. And the increase of these effects depends on the purity of the artist’s motive in the pursuit of art. Every artist who, without reference to external circumstances, aims truly to represent the ideas and emotions which come to him when he is in the presence of nature is in process of his own spiritual development and is a benefactor of his race.”

That’s all fine and good for the 19th century you may say. But what about today? For anyone, seasoned artists or aspiring students, questioning art as a worthy vocation for assisting an embattled planet, painter Alan Feltus offers these thoughts:

“I think art wants to be something people can turn to for a kind of meaning in their lives, or for a calm place within the turbulence of our modern world. Art doesn’t have to explain our situation within the complexity of a chaotic and unstable society. Art can become social commentary, but it can also serve a much needed purpose providing a place of refuge wherein one can find a reason, or justification, for all the battling we have to do, mentally or physically, most of every day of our lives. After all, we love the art of the past for itself, generally being ignorant of the context, the politics, let’s say, of the time and place in which it was made. We hold onto our favorite pieces in our favorite museums or churches, in our books, and we love to be moved by the beauty of something newly found. Art should have that kind of place in our lives. Art should be about transcendence. It should not merely reflect our surroundings like a mirror, adding to the clutter, but become something more wonderful, more meaningful than that. It wants to be remembered and returned to over and over again. Good art feeds us. It is so important.” (From a letter to Arden Eliopoulos, Assisi, May 2, 2001. Courtesy of Alan Feltus’ website.)

“Le Petit Tache:” Divisionist Technique and Optical Mixing

February 7, 2011 § 5 Comments

Impressionist & Divisionist Technique

Landscape was the genre in which divisionist techniques were born and most developed, beginning with Turner and Delacroix who began to exploit the observations and theories of Chevreul and Goethe on the optical mixing of color by painting with distinct touches of unblended paint, side by side, allowing the color to “mix” in the eye.

The work of Turner and Delacroix, as well as that of Goethe and Chevreul in the early 19th century, had a profound impact on Monet, Pissaro, Sisley, Renoir, and others of the group that later became known as “Impressionists.” As students, their academic training taught them to shade forms off into brown and black in the shadows. These young painters could see that shadows were actually colored, and that, in fact, the whole visual field was shimmering with color sensation. Local color, the notion that things have a distinct, unchanging color, was shattered in the new awareness of how color, light, and context influence the perception of color. Their dissatisfaction with the limitations of academic teaching led them out of the studios into nature to work out a new way of painting based on the broken touch.

The technique itself was not new but its application was. The Impressionists built on an academic method widely taught in the ateliers of Paris known as the “petit-tache,” or little touch, a technique of applying unblended touches of color which later would be blended with a soft, badger-hair brush to disguise the effect and create a smoother, more refined look. The Impressionists were reviled, not only for their subject matter, which confronted every day realities of contemporary life as opposed to the classicizing conceits of academic painting, but also for exhibiting finished works with this broken touch, a direct confrontation to the tastes of the day. Seurat, and Signac developed the divisionist technique into the style known as Pointillism, based on their growing interest in the scientific application of color physics to painting.

Painters like Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Serusier, Bonnard, and many others, were less interested in the science of color than they were in its emotional impact, and pushed color saturation into new subjective realms, developing very personal styles that derived from the use of the “petit-tache.”

- Rembrandt

- Frans Hals

- Frans Hals

- Turner

- Turner

- Turner

- Delacroix

- Boudin

- Boudin

- Monet

- Monet

- Monet

- Monet

- Cassatt

- John Singer Sargent

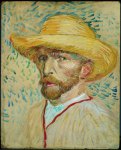

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Van Gogh

- Seurat

- Seurat (detail)

- Seurat

- Seurat

- Signac

- Signac

- Signac

- Signac

- Gauguin

- Serusier

- Bonnard

- Bonnard

- Bonnard

- Jake Berthot

- Jake Berthot

- Jake Berthot

- Chuck Close

- Ann Gale

- Ann Gale

- Alex Kanevsky

- Alex Kanevsky

- Alex Kanevsky