Color Massing

October 27, 2014 § 6 Comments

Look at any slice of nature and the eye is assaulted by a nearly infinite assortment of colors, shapes, textures and surfaces. Is it any wonder that painting from observation can be so vexing at times? Beginning painters often think to start with a detail and can carry on working for hours without considering the structure of the whole. When I point this out they’ll say, “Well, I just haven’t gotten to that part yet.” I came across the picture below in a magazine many years ago. It’s an advertisement for carpeting, but for me it’s emblematic of the problem of getting the cart before the horse. Thinking of painting as a kind of construction site rather than a picture we can draw analogies and insights from the basic logic that inheres in any building process.

When we build a house we don’t start with the curtains. We begin with a big hole in the ground. Into the hole go strong structural elements that flesh out the basic shape of the house, and that will support everything that follows. On the foundation go the partitioning walls that divide and subdivide the total space, followed by the large, interconnecting systems the make the house function: things like plumbing, electrical wires, heating ducts, etc. A builder prioritizes. Without a sense of what logically precedes what, a building would degenerate quickly into a shapeless pile of material. That, in fact, might serve as an apt description of a lot of bad paintings.

The color mass, or what Charles Hawthorne liked to call the “color spots,” is to painting what a foundation is to building. The first task of the painter, assuming he or she has some desire to work from nature, is to sort and prioritize the “blooming, buzzing confusion” of nature into pictorially meaningful color events. The process is one of discerning what is essential and structural in the bewildering display that lies before us, and distinguishing it from what is merely cosmetic. A tree, for example, we know to be composed of millions of tiny leaves and branches. This knowledge alone nearly overwhelms the mind of the beginner. Luckily the eye is more intelligent than the mind, and in the end it’s the eye that enables the painter to begin to sift out the essential color masses of nature into something that actually makes sense on the canvas. Maurice Denis put it this way: “Remember that a painting, before it is a nude, a war horse, or some anecdote, is simply a plane surface covered by color shapes assembled in some order.” If you find it difficult to see these simple masses, you have a built in tool to help you – your own eye.

Close one eye and instantly the three-dimensional world converts to a simple two-dimensional pattern. Squint and all fractional half-tones merge either with the dark end of the value scale or the light end, producing a simple, high-contrast image devoid of 90 percent of the details. The millions of tiny details, all vying equally for attention, are what bog down and frustrate the beginning painter. They actually disguise the larger, structural events that we can use to build a painting. Squinting is like asking all the various tones to choose sides, light or dark.

A further use of this wonderful tool, the eye, is what Joshua Reynolds, in his 17th century Discourses, called “dilating” the vision. When the eye focuses on something the area it takes in is miniscule. We patch together a sense of the world by all these disparate focusings connected by the saccadic movements of the scanning eye. By unfocusing the eye, vision is diffused over a larger area, making the mass colors more apparent. What you see is a collective sensation. The millions of tiny bits that we usually see are gathered up into larger, contrasting color areas that are, effectively, the common denominators of all the many variations of color in our subject. A textured sunlit wall becomes a simple warm color mass. A tree, or a human body, reveals a simple structure of two essential planes, shadow and light. Seeing that, we now have something to take to the palette.

This self-portrait by the Post-Impressionist painter Edouard Vuillard is a kind of textbook in the constructive logic of painting. The head is simplified into a few telling structural color-shapes that evoke the complexity of the subject but stop short of supplying any detail or nuance. Looking at the painting we are confronted by a kind of visual haiku. We are thrilled to see more than is actually there. This is the power of simple color masses in painting. The operation of one color against another puts the whole thing together in a very simple, structural way.

The painter Fairfield Porter was passionate in his study of Vuillard. In his self portrait below you can see how Porter, like Vuillard, simplifies the complex scene before him, succinctly stating the structural breaks between light and dark in his face, his shirt, and legs. Squint at the painting and you can almost imagine the omitted details. Like Vuillard, Porter found poetry in this sort of simplified arrangement of astutely observed color shapes.

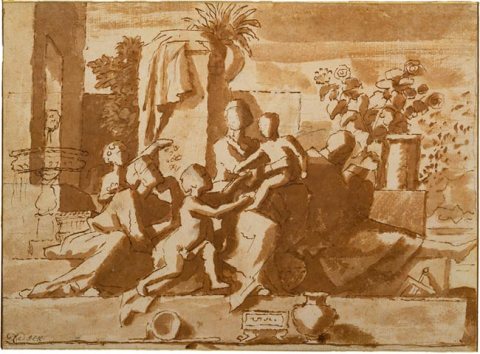

The simple color mass as a construct for building representational paintings can be found throughout the centuries. Leon Battista Alberti’s 1435 treatise on painting advises the painter to follow three simple steps which he calls Circumscription, Composition, and Reception of the Light. Circumscription is the reduction of three dimensional form to simple silhouettes, followed by a subdivision of those shapes into component masses formed by the break between light and shadow. You can see this kind of thinking in Nicolas Poussin’s numerous tone studies from the 17th century.

Working with color massing is not so much a style as it is a strategy for organizing color. Reducing a complex reality to essential contrasts reveals the inherent design in any appearance of nature and gives the painter a different sort of criteria for deciding how to move the painting forward. Every artist, depending on where his or her aesthetic emotion lies, makes choices about how far to develop the painting from this simple abstracted state. It’s like riding a train. You simply choose where to get off. American illustrator Norman Rockwell was admired for his almost photo-realistic images, but if you study the small preparatory oil sketch below it’s evident that this sort of structural search informed his process. It would be a mistake to characterize working with color massing as a style, a school, or an “ism.” It’s simply a tool, and a powerful one, for building paintings because it addresses the fundamental nature of painting, a “plane surface covered by color shapes arranged in a certain order.”

What a helpful reminder of something that should be elementary in my painting process . . . but that I stumble by, so many times, in starting a painting, and then have to reconnect later. This is one of those articles that magically seems to be ‘written just for me’ – especially since you used two of my favorites, Vuillard and Porter, in your examples. Thank You.

So helpful to me. Thank you. Thank you.

Who is the quoted line at the end “a plane surface covered…” attributed to? I presume Hobbs pulled it from somewhere since it is in quotes but not sure.

It’s from Maurice Denis.

This essay on massing is very instructive. Thank you for your explanation and examples.

[…] Hobbs, F. (2014, October 27). Color Massing. Painting OWU. Retrieved from https://paintingowu.wordpress.com/2014/10/27/color-massing/ […]