Fascinating Rythms

April 29, 2019 § Leave a comment

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

“… All you need now is to stand at the window and let your rhythmical sense open and shut, open and shut, boldly and freely, until one thing melts in another, until the taxis are dancing with the daffodils, until a whole has been made from all these separate fragments.” -Virginia Woolf, A Letter to a Young Poet

Children of a certain age are strangely masterful in wielding a brush. They don’t have to be told what to do, or how to do it. Mark-making is a deep, instinctual, and self-sufficient pleasure as old as the human race. Some manage to hold on to the natural feeling for rhythm, movement and relationship in art making as they leave childhood, but too often it becomes buried in the adult whose only model for form-making is the smooth, indiscriminately detailed facture of photography. Re-awakening these dynamic instincts should be as important a goal to the student of painting as learning to see and mix color.

The experiments of artists in the early 20th century are instructive for unpacking this business of rhythm and movement in painting. Abstract forces exist in all painting, and in any view of nature, but they often are disguised, especially to the novice, by the dominance of illusionistic concerns. In the early decades of the 20th century, just as the theories of Einstein began to undo and reshape traditional notions of time and space, Modern art movements such as Cubism, Futurism, De Stjil, and Constructivism began to reorient the focus of painting away from the outward appearance of solid matter to the internal dynamics of pictorial structure. The fractured spaces of George Braque and Picasso, and the reductive verticals, horizontals and diagonals of Theo Van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian began to speak of an energetic reality behind appearances.

Jack Boul, one of my teachers in grad school, made a comment that I think brilliantly frames a fundamental problem of painting. He said, “We sense the structure in early Mondrian. His line first represents a vertical, then a division of the picture space, then a tree. Most people just paint the tree.”

If the Renaissance, and the centuries of pictorial traditions it fostered, were based on the assumption of a solid world composed of discreet entities in a measurable space, the new spirit in painting was informed by the scientific revelation that matter is not solid at all – it’s energy. E=mc2. Painting’s formal language becomes a corollary to this new vision – the structured, dynamic rhythms of the physical universe played out on the artist’s canvas.

Stanley Lewis

September 15, 2013 § Leave a comment

Stanley Lewis is one of the seven artists included in the upcoming exhibition, See It Loud, at the National Academy Museum in New York City.

The Landscape of Contemporary Art

November 2, 2012 § 1 Comment

Critic Dave Hickey says he came into art “because of sex, drugs and artists like Robert Smithson, Richard Serra and Roy Lichtenstein who were “ferocious” about their work. I don’t think you get that anymore. When I asked students at Yale what they planned to do, they all say move to Brooklyn – not make the greatest art ever.”

Making Your Mark, 2

April 18, 2012 § 3 Comments

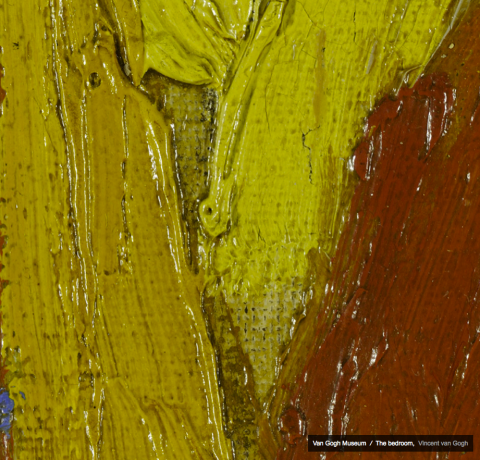

In our early student days, my friends and I would often commiserate about our lack of a consistent “style.” It wasn’t lost on us that when you visited a museum you could always pick out a Van Gogh, or a Monet, or a Franz Kline. It wasn’t just the color, or the subject matter; there was something in the mark-making that always gave it away. Not so our own struggling works. From smooth, polished surfaces to tormented, textured ones, no two paintings of our own seemed to be by the hand of the same artist.

If, like Chuck Close in the previous post, I could write a letter to my younger self, I would say, don’t fret yourself about issues that will take care of themselves in good time. So what if you don’t have a consistent style! Give yourself time to be a student, to try on many different suits of clothes, to wrestle, as an heir, with the important ideas and questions that you’ve inherited until your own questions and ideas begin to emerge. Don’t be in such a hurry to pour yourself in place. “Style” is an ugly word. It connotes things that exist on the surface, things that can be pigeon-holed or categorized, or that can be changed from year to year on a whim. Use it only when speaking about cars, furniture, or fashion, never when speaking of paintings.

Don’t expect the timeline of your development as an artist to conform to the culture’s perverted expectation of instant results. The truth is that your vision, and your craft (yes, I used the “c” word!), take years and years of patient slogging, sometimes with no outward sign of progress. We don’t call it apprenticeship anymore, but that’s what it is. Your taste will change, your intent will change, your understanding and feeling about things will change, and your paintings will change. Let them. One thing you can count on, your work will always reflect who you are. As the saying goes, actions speak louder than words. The marks you make as an artist are as autographic as your handwriting. Just get to work.

Enjoy the hand-writing of these painters in this album: Making Marks.

Making Your Mark

April 11, 2012 § 3 Comments

A chance reading recently from Traces of the Brush: The Art of Japanese Calligraphy, by Louise Boudonnat and Harumi Jushizaki, has got me thinking about something that painters often take for granted, the humble brush; and how something as simple as one’s attitude toward this ubiquitous tool can have such a profound effect on one’s art.

The brush is almost synonymous with both eastern and western painting, but their differing attitudes towards the brush are instructive. In the painting studio at OWU, for example, I routinely pick up brushes abandoned by students, their once supple bristles concretized by dried paint or gesso. I have an entire box of these massacred brushes, the sight of which is sad indeed. To the Japanese painters of past ages, the brush was not just a tool, it was a living thing. A good brush, in the hands of a Hokusai or a Yoshitoshi was an extension of the body itself – a conduit, or a gateway between the invisible and the visible.

From its beginnings at the hands of the brush maker who shaped it, to the end of its useful life, when it would be ritually buried with Buddhist or Shinto rites, an attitude of reverence toward the brush, and to all tools of his art, guided the practice of the Japanese artist. Such reverence and animism invested in material objects seems quaint, even superstitious, to the contemporary western mind which tends to view matter as merely something to be appropriated to one’s purpose and discarded. But, while a proper regard for the tools of one’s trade doesn’t necessarily make the craftsman, it is often the beginning step on the path of becoming one.

From Traces of the Brush: The Art of Japanese Calligraphy:

“The painter, or the draftsman with a brush, is a calligrapher; the marks she makes are a kind of writing made by the individual hand of the artist. Her marks are as unique as her own handwriting.

In eastern art one finds long, venerable traditions of brush calligraphy. The art of painting in eastern cultures is an extension of these traditions, not something completely different. For the artist in China or Japan, to use the brush well demands a complete attention to the particular instrument so that there is no separation of the maker and the made. The brush must become an extension of the body and channels the emotions and the spirit of the mark-maker to the painting surface.

It has its own life force. In Japanese brushes, or wa-fude, the craftsman places two or three hairs at the tip. These form the axis and are like its life line. Indeed, they are called the inochige or “hair of life.” When the inochige are worn, the brush’s energy wanes and its life comes to an end. To underscore the Japanese brush’s living quality and it s similarity to man its parts are known as “the loins” (koshi), “belly” (hara), “shoulders” (kata), and “throat” (nodo).

Just like a person, a brush has its own secret personality that only the calligrapher can get to know over the course of time. Sakaki Bakusan is a contemporary calligrapher who uses the brushes made by the master craftsman Hokodo Shisei. he is fascinated by the vitality and power that he can sense in each one. This is how he describes the experience of using them:

‘When he dips one of his brushes in the ink and touches the paper, it is a bit like mounting a racehorse and understanding and sharing its profound intelligence. He is one with it, as the rider is with his steed. And the brush that runs freely over the pristine space of the sheet listens and hears the calligrapher’s soul. Hokodo creates his brushes out of an intimate knowledge of each artist’s personality. For the elegant and the precious, he makes a supple, pliant brush. For those who fear neither mystery nor danger, he animates it with a ghostly life force that will answer the calligrapher’s own strange feelings. Another more fiery, powerful personality he will entrust with a brush whose lively, surprising character is that of a young woman. Each of the instruments fashioned by Master Hokodo speaks with a singular voice. This one orders: “Use me as often as you can!” This other one is discreet and likes to be forgotten, the better to murmur one morning to the calligrapher, “Today.” “I hate sticky ink!” says one, while another insists, “Wield me with more energy!”‘

… Of all the treasures owned by the scholar, the brush is the most alive but also the most short-lived. To mark this link, this intimacy, the Japanese have a strange, centuries-old custom: brushes are buried in a Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine. Because, for the Japanese, brushes have their own life and soul, the calligrapher watches over their spirit in order to ensure their benevolence.”

The Path Is The Destination

March 23, 2012 § 2 Comments

A metaphor for painting, from the film Down By Law by Jim Jarmusch (1986.) Roberto Begnini draws a “bella finestra” (beautiful window) on their prison cell wall while John Lurie looks on. When he has drawn his window, Begnini asks Lurie, “Do you say, in English, ‘I look AT the window, or do you say, ‘I look OUT the window?'” Lurie replies, “In this case, Bob, you’d say “I look AT the window.”

Jim Jarmusch and Tom Waits

Jim Jarmusch and Tom Waits

Jarmusch, comments on his film, “Down By Law.”

“For me filmmaking, although its very difficult, and it kicks your ass and it’s incredibly hard – you know it’s just as hard to make a bad film as it is a good film; it’s just hard to make a film – but it comes from a place of joy, not of trying to change the world, or express something really deep inside you; it’s more just trying to follow your instincts, things that are moving to you; and to me those are most often mundane ridiculous things, small things, you know, not big dramatic things. It’s really interesting to me, I’ve read reviews and even occasionally, like, dissertations on some of my films that really surprise me because they find all kinds of things that are connected, that are referenced, and half of them I never consciously thought of. So whether those things are in there on a subconscious level, or whether you’re not conscious on any level of them but they somehow wind up in there, is really fascinating.

People think that when you make a film everything that you do is planned, and maybe there are some films made that way. Alfred Hitchcock is famous for story-boarding every single shot in the film but I think you’ll find that most filmmakers, certainly since the 60s, probably don’t use that rigorous structure at all. And I certainly don’t. I consider the script to be a kind of blueprint, and it gives you the shape of the house you’re going to build but it doesn’t really tell you where all the windows are, or what the décor is, or what color the paint on the wall is. You know, it’s kind of a vague idea of the story… I like to have a story that is my departure point, and I try to follow its structure, but also the film has to grow while you make it, or, for me, there’s no point in making it. And, you know, a lot things happen by accident, or things happen by mistake, or the weather interferes so a scene ends up being shot in the rain that wasn’t in the script. Someone improvises some dialogue that you weren’t expecting that is stronger than what you might have had in the script; and all these things kind of combine to make the final film. So it is interesting that, you know, things you think that were planned in a film, often some moments, the most beautiful moments in films, may have happened completely by accident or even by mistake.

One reason that I don’t look at my films again once they’re finished is because I’ve already learned from them what I’m going to learn and by watching them over them again doesn’t teach me anything. There’s a quote by the French poet Paul Valery; he said, ‘a poem is never finished, only abandoned.’ You could edit a film for the rest of your life and still keep changing it and changing it, but at a certain point it leaves your hands and you send it off to military school, or whatever; it’s gone, it’s on its own, you know. You kick it out of the house and it’s gone, and it has to live in the world itself. I have a personal motto that it’s hard to get lost if you don’t know where you’re going. I really believe that intuition is the real guide. Therefore to me my work as a filmmaker is a process and there is no destination; it’s like the Buddhist saying, the path is the destination. I really feel that way. I loved it when they asked Kurosawa, when he was in his eighties, when would he stop making films, and he said, ‘as soon as I figure out how to do it.’

It’s very hard to say specific things you learn from each particular film, but the experience of making films is the end result. And the film itself is something you kind of leave in your wake as the result of the process.” (From the DVD release of Down By Law.)

The Three Dimensions of Color

March 3, 2012 § Leave a comment

Goethe’s color wheel

The color-wheel. What would painters do without it’s simple graphic display of basic color theory? An intuitive leap by none other than Sir Isaac Newton brought the color-wheel into being, and some form of it has underpinned the teaching of color theory ever since. Today it seems that a cottage industry of color-wheel bashing has sprung up, coinciding, I suspect, with the explosion of How-To art books and blogs. If you want to sell something, first create a “New! Improved!” alternative.

There are blogs on color theory which denigrate the color-wheel model as an obsolete product of the Enlightenment that no longer matches what we now know about color perception. Never mind that the “newer, simpler” explanations they offer inevitably fall back on the basic tropes of the color wheel to discuss important concepts, such as complements being “across the wheel.” One notable book published a few years ago, Blue and Yellow Don’t Make Green, is petulant about the supposed failure of traditional color theory and uses that as a pretext for page after page of reproductions, printed in fugitive dyes, showing what actually happens when you mix this pigment with that pigment. Most art students will have discovered these anomalies in the color palette within their first two years of study. Everything that happens on the palette can be traced back to the basic theories of the color circle. If you locate the relative position on the wheel of any two colors, with respect to their hue, temperature, and intensity, and draw a line between them you can easily see why two particular pigments produce the color qualities they do. It’s a simple equation of distance.

The color-wheel model persists because it contains the most useful information in the smallest package. It’s not perfect – lacking a third dimension it can only demonstrate two properties of color, hue and intensity – but basic color-wheel concepts still hold true. The only failure is forgetting to bring theory back to practice. No amount of color theory can substitute for familiarity with the palette.

A 3-dimensional model of color movement: the Munsell color tree

For a clear, concise demonstration of color mixing for painters check out this video by Robert Gamblin, the founder of Gamblin Colors. Using a computer animated 3-D model patterned on the Munsell color system, Gamblin shows the interrelationship of the three main properties of color: hue, value, and intensity by linking them to the three dimensions of “color space.”

18th Century Wisdom

February 18, 2012 § 3 Comments

Whenever I visit art museums I usually walk as quickly as I can past the paintings of Sir Joshua Reynolds and his ilk (Henry Raeburn excepted) to get to Constable and Turner. Reynolds has never been, nor will he ever be, among my pantheon of painting gods. (The self-portrait above is an exception.) Perhaps it’s the knighthood that puts me off. “Sir” seems an ill-fitting prefix to the name of an artist, the archetypical rebel against rules, a free agent of consciousness unbeholden to institutions of any kind. Frank Auerbach and David Hockney refused the honor, as did David Bowie. Sir Mick Jagger’s acceptance of the title has a certain slyness about it, as if he’s winking secretly. In truth, it’s not the “Sir” I have a problem with. It’s the paintings.

Sir Joshua’s contribution to art history of course cannot be diminished. As a founding member and first president of the Royal Academy, a post he held from 1768 to 1792, Reynolds did much to elevate the status of the artist in society and to preserve traditional studio knowledge and its teaching. If the work of his hand seems too “official,” too conformative to the grand-style conceits of his day to hold one’s interest for very long, the work of his pen is another matter.

Reynolds’ Discourses on Art, delivered as a series of lectures from 1769 to 1790 to students of the Royal Academy, are rich indeed, and still speak to the concerns of students of painting today, if you have the patience to parse the meat from the embroidery of 18th century rhetoric. Neither Reynolds, nor his audience, would even faintly understand what we mean today by the term “Attention Deficit Disorder.” Ideas were things to be taken down with a quill pen on paper, not something to Google and bookmark for later. Like anything valuable, you have to work at it to get the benefit.

Not every topic or drift of thought in the Discourses will resonate today. Even in his own time there were critics. William Blake wrote “Lies!,” “Villainy!” and “Nonsense!” in the margins of his copy of the Discourses. The Pre-Raphaelites dubbed Reynolds, “Sir Sloshua.” His critics notwithstanding, anyone who has struggled under the modern “Art Can’t Be Taught” zeitgeist to discover or re-discover useful studio knowledge will appreciate the practical wisdom of Reynolds teaching.

My favorite of the Discourses is number XI, in which Reynolds addresses himself to the problem of “finish” and the relationship of parts to the whole. Many of the ideas he articulates can be found in similar statements by later artists. There are echoes of Reynolds in Matisse’s assertion that “a work of art must carry in itself its complete significance and impose it upon the beholder even before he can identify the subject matter.” Or his statement: “All that is not useful in the picture is detrimental. A work of art must be harmonious in its entirety; for superfluous details would, in the mind of the beholder, encroach upon the essential elements.”

Here is an abstract of the essential points of Discourse XI. Quotation marks enclose direct phrasing from the original text. My comments are enclosed in parentheses.

- There is “genius” in the power of expressing the subject as a whole, so that the general effect and power of the whole impresses the mind, before the subordinate parts.

- There are “great characteristic distinctions” (contrasts, masses) in all subjects which are more than just accumulations of small particulars or details… Putting in details which do not assist the expression of the main characteristic is “worse than useless, it is mischievous” because it detracts attention from the whole.

- When the general effect is presented skillfully it appears to represent the object in a more lively way.

- This raises the question of why we are not always pleased by exact imitation (wax works, e.g.). Pleasure is not proportionate to amount of detail. On the contrary – we are pleased by seeing ends accomplished by seemingly inadequate (or surprising) means.

- Excellence in color, drawing, or modeling is only attained with the habit of looking upon objects at large and observing the effect on the eye when it is “dilated” (out-of-focus), and employed upon the whole without seeing any of the parts distinctly. This is how to obtain the “ruling characteristic” (the “macchia,” the “notan,” or the tonal structure) and how to learn to put it down by “dextrous methods” (with economy.)

- The work of great masters is not in the finish but in their ability to see everything as one (interconnected) whole.

- Titian knew how to mark by a few strokes the general image and character of whatever object he painted. Took great care to express the masses of color, light & shade, which convey the effect of completeness. Lacking this structure the picture may contain much finishing of details but will always look unfinished (disorganized, lacking unity or coherence.)

- It is vain to attend to all the variations of hue if the general hue (the key) is lost, or to finish the smaller parts if the greater masses are not observed, or if the whole is not put together well.

- Affecting dexterity without selection or a discriminating eye leads to what Vasari calls “goffe pitture,” or “absurd, foolish pictures.”

- Works of great art, like poetry, raises by the power of the language the most mundane things. This is the power of great artists. No subject is too insignificant.

- On “finishing:” Not recommending a lack of detail, for the judicious detail will often convey the convincing sense of truth. This should be left to the painter’s taste and judgment. But there is a distinction between “essential and subordinate powers,” or what draws the chief attention.

- Condemns another kind of finishing: the indiscriminate blending and gradating of colors (over-modeling). The true effect of representation consists very much in preserving the same proportion of sharpness and softness found in the subject (attention to edges, or meeting of masses).

- The value of drawings which seem unfinished or rough is that they give the idea of the whole, dextrously expressed.

- A landscape painter attending to the masses of foliage would produce a better likeness than a painter who thought to imitate each leaf.

- When a painter knows his subject he knows what to omit as well as what to put in. This skill in leaving out is a great part of knowledge and wisdom.

- The excellence of portrait painting, and the likeness itself, depends more on observation of the general effect of light and shade than on exactitude in particulars. The chief attention is given to planting the features in their proper places. A painter may labor to refine the particulars but never forget to examine and weigh whether in finishing he is not destroying the general effect.

- On subject matter: In half the pictures in the world, the subject can be valued only as an occasion which sets the artist to work. This shows how much our attention is engaged by the art alone.

- Subject matter in great paintings is often of no account. The interest and power of painting lies in the dexterity of the artist under the command of this “comprehensive faculty” (the ability to regard the subject abstractly as a whole rather than as an inventory of disconnected parts.) This is the power which raises mechanical dexterity above the common level (mere skill or technique). It becomes an instance in which mind predominates over matter by contracting into one whole the multifarious expressions of nature. A greater truth may be expressed in a few lines or touches if one regards the whole, than in the most laborious finishing of the parts when this is disregarded.

- This is not to encourage carelessness, lack of finish or exactness, but to point out the best kind of exactness. Diligence in study and practice is needed to acquire a sense of the whole. It requires the painter’s entire mind, whereas finishing details may be done while the mind is distracted.

- The “ease and laziness” of highly finishing the parts, producing the “laborious effects of idleness.”

- When diligence is properly employed work cannot be too finished but, nine times out of ten, excessive labor in the detail has been “pernicious” to the general effect (unit of the whole).

- The need to give “right direction to your industry.” To acquire the habit and art of seeing nature in an “extensive view,” in its relative proportions and its due subordination of parts (the hierarchy or relative dominance and subordination of the various parts of the composition).

- The purpose of studying masters is to understand the great principles which the work embodies. Consider the works only as a means of teaching one the art of seeing nature. The great business of study is to “form a mind,” adapted to and adequate to all occasions.

A Gang Theory of Education

January 26, 2012 § 2 Comments

I teach an art seminar for seniors at Harvard. One peculiarity of my own education is that I barely have any. I’m one of those ’60s dropouts you read about, and I never took an art course in my life. This background made me incredibly nervous about teaching, but it has gone all right.

I’m fascinated by the problem of teaching artists in college, because, What is an artist? An artist, in my experience, is a man or woman of unusual talent and peculiar, highly individual sensibility, with an independent and probably contrarian mind, driven by mysterious passions for which another word is neurosis. In getting from point A to point B, the neurotic goes via point Q. It’s in that roundabout that people are either completely crippled and hopeless in life, or highly creative.

The artist is a strange being. I think it’s safe to say that a real artist is conscious of having a personal singularity that is partly a blessing and partly a curse. An artist enjoys and suffers from isolation. As solitude, isolation can nurture. It can also destroy.

Artists are people who are subject to irrational convictions of the sacred. Baudelaire said that an artist is a child who has acquired adult capacities and discipline. Art education should help build those capacities and that discipline without messing over the child. By child, I do not mean childish behavior — I mean the irrational conviction of the sacred.

Everything that would begin to make somebody a good student would tend to make him or her a poor artist, and vice versa. I’m well aware of this as a problem — particularly at Harvard, because at Harvard, the students are, by definition, the best in the world. That’s who they select. It’s certainly a luxury for teaching. The students can actually all write, which is astounding. One of my fellow teachers there once said, “It’s amazing, these kids. You can throw the stick as far as you want to in the swamp, and they’ll bring it back every time.” But along with that comes a cageyness and an all-too-ready ability to beguile teachers.

I have what I call a “gang theory” of education. All gangs are formed by individuals who, for one reason or another, are misfits, wander to the margin by themselves, discover each other, discover other people like themselves. They bond together. If all they have in common is that alienation, they’re a very dangerous group of kids. But if they have some aspiration in common, they can be intensely creative. In a way, everybody does this growing up. Every age group is a cohort — particularly in our culture, which is intensely generational. When we grow up, we tend to trust only those who share our exact historic and cultural period, who watch the same television shows with the same attitudes. Childhood, for everyone, is more than formative. It’s a trove of spiritual material for a lifetime. But this is especially true of artists.

Gang members are extremely competitive, but not with each other. They pool their resources, their information, their knowledge, and attack the world. Teams work this way, too, but I like the concept of the gang because, with art, there has to be an element of condoned anarchy. You can’t measure creative development by criteria that are like crisply executed football plays. Coaching a gang, it seems to me, one must concede the role of judging individual worth to the group.

In a gang — of art students, say — everybody knows without saying who is the best. It’s very primitive, very hierarchical, in the way wild animals are hierarchical. Everyone knows who’s best, who’s second best. There’s a lot of doubt about who’s third best, because everybody else thinks they’re third best. Except for one person who is absolutely hopeless. This person, as a mascot and scapegoat, is cherished by everyone.

The problem is: How do you nurture a gang in academe? I don’t think academia should take much responsibility for this. A college education is, and should be, people wanting typical careers in the structure of the world. Education must not distort itself in service to the tiny minority of narcissistic and ungrateful misfits who are, or might be, artists.

What I want to know from students, and I ask them right away, is, What do you want? I don’t care what it is. I want to help you get it. If you don’t know what you want, that’s normal at your age. And I will feel your pain — up to a point. But if you don’t know what you want past a certain point, then we’re just chattering, we’re wasting the taxpayers’ or your parents’ money. This is fine. It happens all the time. But it’s depressing.

My aim is to help kids realize that they’re artists already, or that maybe they don’t really want to do it, which is more than fine. They’ve saved themselves a lot of grief, and they can get on with their lives. I tell them that I’m not interested in educating their minds, I’m interested in sophisticating them, which is different. Sophistication is knowledge that’s acquired in the course of having a purpose. You know why you want the information at the moment that you put your hand on it. You’re not just storing it up for a rainy day.

And what are you learning about in my seminar? You’re learning about the course of art, the course of society, the course of the world, the course of your life. You are joining a conversation. You do not prepare to join a conversation. You come up to the edge of it and listen and kind of get the beat, then you jump in. And maybe if you jump in too soon, everyone’s going to give you a look and you’ll slink off and come back later. It’s to get this conversation going among a group of people, when they’re students — that’s what I’d like to be able to do. It’s a very messy process.

Aspects of sophistication. Love and style. Spirituality and street smarts. Why do you need street smarts? Shrewdness? Toughness? It’s to protect something soft that is going to be in danger if it’s exposed at the wrong time and place. It’s to protect a soul. But to protect your soul, you have to have one to start with. There’s nothing that can be done about that in a seminar.

The role of the teacher in gang theory is to throw red meat through the bars of their cage. My particular expertise is savviness about the New York art world, so that’s what I share. With another teacher, it would be something else. There’s nothing innately relevant or innately irrelevant to an artist. If their minds and spirits can’t put the stuff in order, then they’re not artists. Very often the flashiest, most seemingly talented person turns out to be not an artist at all, and some hopeless klutz ends up being Jackson Pollock.

A lot of education is like teaching marching; I try to make it more like dancing. Education is this funny thing. You deal for several years with organized information, and then you go out into the world and you never see any of that ever again. There’s no more organized information. I’m trying to establish within my seminars disorganized information, which students can start practicing their moves on.

© Peter Schjeldahl. First given at a conference on Liberal Arts and the Education of Artists in 1998, transcribed and published by Chronicles of Higher Education, 11/27/98. Bio courtesy of New Yorker Magazine.

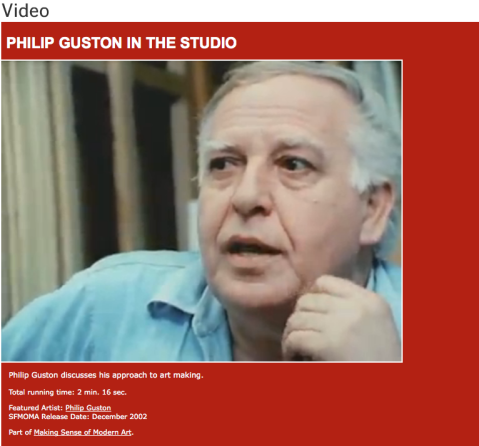

Paint & Process: Philip Guston in the Studio

January 26, 2012 § 9 Comments

“Destruction of paintings is very interesting to me and almost crucial. Sometimes I find that what I destroyed five years ago I’ll paint now, as if when the thing first appears you’re not ready to accept it. There’s some mysterious process here that I don’t even want to understand. I know that if I stopped painting and became a psychologist of the process of making I would probably understand it more but it wouldn’t do me any good. I don’t want to understand it like that, analytically. But I know that there is some working out that takes place in time but it’s not given to me to perfectly understand it; it’s illegal.

The first thing always looks good, then you start doubting it. I started this painting a few days ago; it went alright. It was almost finished in a day. But I came in late that night and I liked the left part. I didn’t like the right part. I started changing the right part and something happened that felt better than the left part, so then I changed the left part and before I knew it, the whole painting vanished! The painting that was almost finished didn’t look bad; it looked alright but it looked almost too good. It was as if I hadn’t experienced anything with it. It was too much of a Painting. I don’t mean that I need to struggle always with it… but it felt to me as if it were additions – this AND that AND this AND that. What I’m always seeking is some great simplicity where the whole thing is just there and can’t be just this and that and this and that.”

Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Art

Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Art