Fascinating Rythms

April 29, 2019 § Leave a comment

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

“… All you need now is to stand at the window and let your rhythmical sense open and shut, open and shut, boldly and freely, until one thing melts in another, until the taxis are dancing with the daffodils, until a whole has been made from all these separate fragments.” -Virginia Woolf, A Letter to a Young Poet

Children of a certain age are strangely masterful in wielding a brush. They don’t have to be told what to do, or how to do it. Mark-making is a deep, instinctual, and self-sufficient pleasure as old as the human race. Some manage to hold on to the natural feeling for rhythm, movement and relationship in art making as they leave childhood, but too often it becomes buried in the adult whose only model for form-making is the smooth, indiscriminately detailed facture of photography. Re-awakening these dynamic instincts should be as important a goal to the student of painting as learning to see and mix color.

The experiments of artists in the early 20th century are instructive for unpacking this business of rhythm and movement in painting. Abstract forces exist in all painting, and in any view of nature, but they often are disguised, especially to the novice, by the dominance of illusionistic concerns. In the early decades of the 20th century, just as the theories of Einstein began to undo and reshape traditional notions of time and space, Modern art movements such as Cubism, Futurism, De Stjil, and Constructivism began to reorient the focus of painting away from the outward appearance of solid matter to the internal dynamics of pictorial structure. The fractured spaces of George Braque and Picasso, and the reductive verticals, horizontals and diagonals of Theo Van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian began to speak of an energetic reality behind appearances.

Jack Boul, one of my teachers in grad school, made a comment that I think brilliantly frames a fundamental problem of painting. He said, “We sense the structure in early Mondrian. His line first represents a vertical, then a division of the picture space, then a tree. Most people just paint the tree.”

If the Renaissance, and the centuries of pictorial traditions it fostered, were based on the assumption of a solid world composed of discreet entities in a measurable space, the new spirit in painting was informed by the scientific revelation that matter is not solid at all – it’s energy. E=mc2. Painting’s formal language becomes a corollary to this new vision – the structured, dynamic rhythms of the physical universe played out on the artist’s canvas.

Color Massing

October 27, 2014 § 6 Comments

Look at any slice of nature and the eye is assaulted by a nearly infinite assortment of colors, shapes, textures and surfaces. Is it any wonder that painting from observation can be so vexing at times? Beginning painters often think to start with a detail and can carry on working for hours without considering the structure of the whole. When I point this out they’ll say, “Well, I just haven’t gotten to that part yet.” I came across the picture below in a magazine many years ago. It’s an advertisement for carpeting, but for me it’s emblematic of the problem of getting the cart before the horse. Thinking of painting as a kind of construction site rather than a picture we can draw analogies and insights from the basic logic that inheres in any building process.

When we build a house we don’t start with the curtains. We begin with a big hole in the ground. Into the hole go strong structural elements that flesh out the basic shape of the house, and that will support everything that follows. On the foundation go the partitioning walls that divide and subdivide the total space, followed by the large, interconnecting systems the make the house function: things like plumbing, electrical wires, heating ducts, etc. A builder prioritizes. Without a sense of what logically precedes what, a building would degenerate quickly into a shapeless pile of material. That, in fact, might serve as an apt description of a lot of bad paintings.

The color mass, or what Charles Hawthorne liked to call the “color spots,” is to painting what a foundation is to building. The first task of the painter, assuming he or she has some desire to work from nature, is to sort and prioritize the “blooming, buzzing confusion” of nature into pictorially meaningful color events. The process is one of discerning what is essential and structural in the bewildering display that lies before us, and distinguishing it from what is merely cosmetic. A tree, for example, we know to be composed of millions of tiny leaves and branches. This knowledge alone nearly overwhelms the mind of the beginner. Luckily the eye is more intelligent than the mind, and in the end it’s the eye that enables the painter to begin to sift out the essential color masses of nature into something that actually makes sense on the canvas. Maurice Denis put it this way: “Remember that a painting, before it is a nude, a war horse, or some anecdote, is simply a plane surface covered by color shapes assembled in some order.” If you find it difficult to see these simple masses, you have a built in tool to help you – your own eye.

Close one eye and instantly the three-dimensional world converts to a simple two-dimensional pattern. Squint and all fractional half-tones merge either with the dark end of the value scale or the light end, producing a simple, high-contrast image devoid of 90 percent of the details. The millions of tiny details, all vying equally for attention, are what bog down and frustrate the beginning painter. They actually disguise the larger, structural events that we can use to build a painting. Squinting is like asking all the various tones to choose sides, light or dark.

A further use of this wonderful tool, the eye, is what Joshua Reynolds, in his 17th century Discourses, called “dilating” the vision. When the eye focuses on something the area it takes in is miniscule. We patch together a sense of the world by all these disparate focusings connected by the saccadic movements of the scanning eye. By unfocusing the eye, vision is diffused over a larger area, making the mass colors more apparent. What you see is a collective sensation. The millions of tiny bits that we usually see are gathered up into larger, contrasting color areas that are, effectively, the common denominators of all the many variations of color in our subject. A textured sunlit wall becomes a simple warm color mass. A tree, or a human body, reveals a simple structure of two essential planes, shadow and light. Seeing that, we now have something to take to the palette.

This self-portrait by the Post-Impressionist painter Edouard Vuillard is a kind of textbook in the constructive logic of painting. The head is simplified into a few telling structural color-shapes that evoke the complexity of the subject but stop short of supplying any detail or nuance. Looking at the painting we are confronted by a kind of visual haiku. We are thrilled to see more than is actually there. This is the power of simple color masses in painting. The operation of one color against another puts the whole thing together in a very simple, structural way.

The painter Fairfield Porter was passionate in his study of Vuillard. In his self portrait below you can see how Porter, like Vuillard, simplifies the complex scene before him, succinctly stating the structural breaks between light and dark in his face, his shirt, and legs. Squint at the painting and you can almost imagine the omitted details. Like Vuillard, Porter found poetry in this sort of simplified arrangement of astutely observed color shapes.

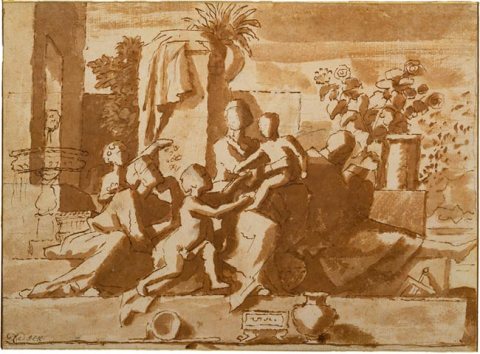

The simple color mass as a construct for building representational paintings can be found throughout the centuries. Leon Battista Alberti’s 1435 treatise on painting advises the painter to follow three simple steps which he calls Circumscription, Composition, and Reception of the Light. Circumscription is the reduction of three dimensional form to simple silhouettes, followed by a subdivision of those shapes into component masses formed by the break between light and shadow. You can see this kind of thinking in Nicolas Poussin’s numerous tone studies from the 17th century.

Working with color massing is not so much a style as it is a strategy for organizing color. Reducing a complex reality to essential contrasts reveals the inherent design in any appearance of nature and gives the painter a different sort of criteria for deciding how to move the painting forward. Every artist, depending on where his or her aesthetic emotion lies, makes choices about how far to develop the painting from this simple abstracted state. It’s like riding a train. You simply choose where to get off. American illustrator Norman Rockwell was admired for his almost photo-realistic images, but if you study the small preparatory oil sketch below it’s evident that this sort of structural search informed his process. It would be a mistake to characterize working with color massing as a style, a school, or an “ism.” It’s simply a tool, and a powerful one, for building paintings because it addresses the fundamental nature of painting, a “plane surface covered by color shapes arranged in a certain order.”

Staying Neutral

March 7, 2014 § 3 Comments

Experience teaches us that limitation is the essence of creativity. Like a single flute playing in an echo chamber, the sounded notes of a few colors, a few shapes or lines set up visual resonances within the bounding space of the rectangle, multiplying complexity in unforeseen ways through their endless permutations. Using color in a limited way is a great way to explore this phenomenon. Here are some examples of works that choose to proscribe the range of color intensity, exploring the neutral zone that lies in the center of the color circle. Because of the relativity of color, the rainbow continues to assert itself but in a lowered intensity key. Color appears, not through pigmentation, but through optical relationships. Absence becomes presence.

Stanley Lewis

September 15, 2013 § Leave a comment

Stanley Lewis is one of the seven artists included in the upcoming exhibition, See It Loud, at the National Academy Museum in New York City.

Rackstraw Downes

April 19, 2012 § 5 Comments

“When I… started painting from observation, one of the reasons was that I didn’t want to be so damn self-conscious about my paintings… Why not just look at something and paint it the way it is? Plop! And that’s what I did.

People often say to me, why do you pick such banal subjects, and I don’t understand that at all. They don’t seem to me to be banal in the least. They’re full of magic.

I came from a very flamboyant household, very theatrical – a very histrionic household. Everything was exaggerated; you never knew what anyone meant, and I didn’t like it. And I didn’t trust my own histrionics either, or strong affect, or whatever it is… in my paintings I try to get all that out and state it exactly – ‘no no, that’s not the way that air conditioner sits in that window. Do it again, Downes, and get it right this time, the way it really is!’ And I love that! I love feeling I have now got it, banal or not, I don’t care.

The detail comes in because you have to figure out how to move from here to here; then to here and to here… you make this block without any windows and you’re not sure whether it really is comfortably that size. As soon as you get those windows in there you get clearer and clearer and clearer about what it is. And in order to move about and keep these things in proportion I need all these things.

It’s my job to find places that answer to some internal need. I think that there’s this internal need before you get to the place and that the place answers the need.

…Could you paint a mountain without being sentimental about mountains, without falling victim to the mountain rhetoric; you know: look at this tremendous canyon, it’s so deep, and look at this terrifying crag up over your head, and all that business… I’m not interested in rhetoric at all.

I think that artists, or people who are active in another art form, even if it be writing or music… are often very, very perceptive critics of a different art form… a writer writing about painting or something, because they realize the limitations of criticism. Criticism can’t do everything, it can’t explain everything, and it can’t make certainties. There are no certainties in art.

There was a statement of Stendhal’s he wrote to his sister… “Only write on matters that you feel very strongly about. When you put them into words, try to do it as though you didn’t want anyone to notice.” I thought that was stunningly brilliant, and I felt exactly the same way.

I will say this… that all of us that are painters or artists or poets, or whatever it is, we spend quite a big chunk of every day doing the thing we really want to do. That cannot be said by lots of people.

– Rackstraw Downes, from video and interview by Betty Cunningham Gallery, 2007.

Chuck Close: Notes to My Younger Self

April 12, 2012 § Leave a comment

Courtesy of CBS News

Courtesy of CBS News

“This is a note to myself at age 14:

I was in the eighth grade and was told not to even think about going to college. I couldn’t add or subtract, never could memorize multiplication tables, was advised against taking algebra, geometry, physics, chemistry. Since I was good with my hands I was advised to aim for trade school, perhaps body and fender work.

Never let anyone define what you are capable of by using parameters that don’t apply to you. I applied to a junior college in my hometown with open enrollment, got in and embarked on a career in the visual arts. Virtually everything I’ve done is influenced by my learning disabilities. I think I was driven to paint portraits to commit images of friends and family to memory. I have face blindness, and once a face is flattened out I can remember it much better.

Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and get to work. Every great idea I’ve ever had grew out of work itself. Sign on to a process and see where it takes you. You don’t have to invent the wheel every day. Today you’ll do what you did yesterday, tomorrow you’ll do what you did today. Eventually you’ll get somewhere. No one gets anywhere without help. Mentors, including your parents, can make you feel special even when you’re failing in other areas. Everyone needs to feel special.

My father died when I was eleven and that was the tragedy of my life, a horrible thing to happen when you’re so young. Oddly enough, there was a gift in this tragedy. I learned very early in life that the absolute worst thing can happen to you and you will get past it and you will be happy again. Losing my father at a tender age was extremely important in being able to accept what happened to me later when I became a quadriplegic.

If you’re overwhelmed by the size of a problem, break it down into many bite-size pieces. Quadriplegics don’t envy the able-bodied, we envy paraplegics. We think they’ve got a much easier row to hoe. There’s always someone worse off than you. I’m confident that no artist has more pleasure, day in and day out from what he or she does, than I do.”

Making Your Mark

April 11, 2012 § 3 Comments

A chance reading recently from Traces of the Brush: The Art of Japanese Calligraphy, by Louise Boudonnat and Harumi Jushizaki, has got me thinking about something that painters often take for granted, the humble brush; and how something as simple as one’s attitude toward this ubiquitous tool can have such a profound effect on one’s art.

The brush is almost synonymous with both eastern and western painting, but their differing attitudes towards the brush are instructive. In the painting studio at OWU, for example, I routinely pick up brushes abandoned by students, their once supple bristles concretized by dried paint or gesso. I have an entire box of these massacred brushes, the sight of which is sad indeed. To the Japanese painters of past ages, the brush was not just a tool, it was a living thing. A good brush, in the hands of a Hokusai or a Yoshitoshi was an extension of the body itself – a conduit, or a gateway between the invisible and the visible.

From its beginnings at the hands of the brush maker who shaped it, to the end of its useful life, when it would be ritually buried with Buddhist or Shinto rites, an attitude of reverence toward the brush, and to all tools of his art, guided the practice of the Japanese artist. Such reverence and animism invested in material objects seems quaint, even superstitious, to the contemporary western mind which tends to view matter as merely something to be appropriated to one’s purpose and discarded. But, while a proper regard for the tools of one’s trade doesn’t necessarily make the craftsman, it is often the beginning step on the path of becoming one.

From Traces of the Brush: The Art of Japanese Calligraphy:

“The painter, or the draftsman with a brush, is a calligrapher; the marks she makes are a kind of writing made by the individual hand of the artist. Her marks are as unique as her own handwriting.

In eastern art one finds long, venerable traditions of brush calligraphy. The art of painting in eastern cultures is an extension of these traditions, not something completely different. For the artist in China or Japan, to use the brush well demands a complete attention to the particular instrument so that there is no separation of the maker and the made. The brush must become an extension of the body and channels the emotions and the spirit of the mark-maker to the painting surface.

It has its own life force. In Japanese brushes, or wa-fude, the craftsman places two or three hairs at the tip. These form the axis and are like its life line. Indeed, they are called the inochige or “hair of life.” When the inochige are worn, the brush’s energy wanes and its life comes to an end. To underscore the Japanese brush’s living quality and it s similarity to man its parts are known as “the loins” (koshi), “belly” (hara), “shoulders” (kata), and “throat” (nodo).

Just like a person, a brush has its own secret personality that only the calligrapher can get to know over the course of time. Sakaki Bakusan is a contemporary calligrapher who uses the brushes made by the master craftsman Hokodo Shisei. he is fascinated by the vitality and power that he can sense in each one. This is how he describes the experience of using them:

‘When he dips one of his brushes in the ink and touches the paper, it is a bit like mounting a racehorse and understanding and sharing its profound intelligence. He is one with it, as the rider is with his steed. And the brush that runs freely over the pristine space of the sheet listens and hears the calligrapher’s soul. Hokodo creates his brushes out of an intimate knowledge of each artist’s personality. For the elegant and the precious, he makes a supple, pliant brush. For those who fear neither mystery nor danger, he animates it with a ghostly life force that will answer the calligrapher’s own strange feelings. Another more fiery, powerful personality he will entrust with a brush whose lively, surprising character is that of a young woman. Each of the instruments fashioned by Master Hokodo speaks with a singular voice. This one orders: “Use me as often as you can!” This other one is discreet and likes to be forgotten, the better to murmur one morning to the calligrapher, “Today.” “I hate sticky ink!” says one, while another insists, “Wield me with more energy!”‘

… Of all the treasures owned by the scholar, the brush is the most alive but also the most short-lived. To mark this link, this intimacy, the Japanese have a strange, centuries-old custom: brushes are buried in a Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine. Because, for the Japanese, brushes have their own life and soul, the calligrapher watches over their spirit in order to ensure their benevolence.”

Alan Feltus: Words on Art

April 1, 2012 § 6 Comments

I first met Alan Feltus when I was a graduate student at at American University where he taught until he and his wife, painter Lani Irwin, decided to move to Italy, near Assisi, to live, work, and raise their children. I often sat in on Alan’s figure drawing classes, absorbing his deep love of painting, particularly the work of the Italian masters. My strongest memories are of Alan sitting on the model stand before the model took the stage, surrounded by art books which he would open to certain pictures and discuss with the class, like a rabbi giving an exegesis on sacred texts.

Here are some of his thoughts about art, which you can read in greater detail, along with essays written about his work by others, from his website.

“February 2003, Assisi”

These paintings are about many things and at the same time about nothing more than painting itself. They don’t have narrative content; they don’t tell stories. What the figures communicate is not knowable, not to me and therefore not to the viewer. Or perhaps I should say what is communicated is open to interpretation and as such there are endless meanings. Endless possible readings. They are quiet images with unspoken, and elusive meanings. They are abstract in the same way instrumental music is abstract. They convey something. They create a certain mood. We feel something when we slow down and focus on what a painting says. They are readable the way the world is readable to us. We need not ask how we should understand everything we observe.

I paint without models. I draw upon many kinds of sources, but largely those painters, from ancient to modern, whose works have taught me most throughout my career. They tend to be the painters who structure their paintings tightly.They are masters of much more than that but, it seems, always masters of composition. More than not, they also painted from within. Or perhaps they, like myself, are observering art and nature all the time while not in the studio, and then while painting rely on what has been internalized. Each of us will have a unique compilation of remembered sensations and it is how this material shapes our work that will distinguish my paintings from those of the next painter. We really don’t have all that much control over what we produce when we work from within.

What unfolds on the canvas evolves slowly. My paintings take weeks or months to complete. They have many layers of changes and then more layers of refinement before every element feels right in relation to every other. Form gradually defines itself in light, and light and color begin to work.

(From a letter to Arden Eliopoulos. Assisi, May 2, 2001).

I think art wants to be something people can turn to for a kind of meaning in their lives, or for a calm place within the turbulance of our modern world. Art doesn’t have to explain our situation within the complexity of a chaotic and unstable society. Art can become social commentary, but it can also serve a much needed purpose providing a place of refuge wherein one can find a reason, or justification, for all the battling we have to do, mentally or physically, most of every day of our lives. After all, we love the art of the past for itself, generally being ignorant of the context, the politics, let’s say, of the time and place in which it was made. We hold onto our favorite pieces in our favorite museums or churches, in our books, and we love to be moved by the beauty of something newly found. Art should have that kind of place in our lives. Art should be about transcendence. It should not merely reflect our surroundings like a mirror, adding to the clutter, but become something more wonderful, more meaningful than that. It wants to be remembered and returned to over and over again. Good art feeds us. It is so important.

(From a letter to Joseph Jennings, July 27, 2000, Assisi)

Yesterday I struggled more with the painting on my easel. There have been things about the space that hadn’t been working. Maybe it made some advances yesterday. Painting can move very slowly for me. Lani’s as well. But painting is the one thing I seem to have endless patience with. I know it wants to move slowly at times. There are so many days when nothing is resolved yet those days are necessary in order to progress beyond whatever it is that holds a painting back. The painting needs to reflect an inner self. It results from a meditative state, it seems. And those sleepy days at the easel when nothing seems to move ahead are essential. You understand all that quite instinctively, it seems to me.